Are We Close to Finding Planet 9?

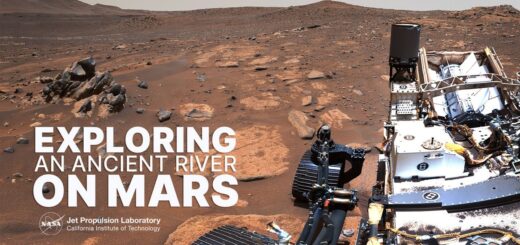

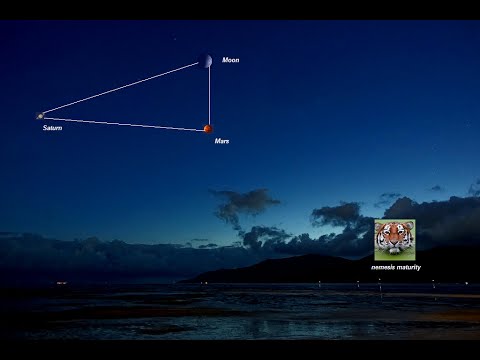

Thanks to Brilliant for sponsoring today’s video. My Very Educated Mother Just Showed Us Nine Planets. This phrase was one of the mnemonics designed to help me in my youth to remember the names of the planets in our Solar System. Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, and Pluto. It’s a little outdated, as in 2006 Pluto lost its status as the Ninth Planet, meaning my very educated mother could no longer show us nine planets, only eight. But what if I was to tell you that there might exist another planet, an object 5 times the size of the Earth, that is floating out in the furthest reaches of our solar system? Perhaps my mother knows what she’s talking about, after all. I’m Alex McColgan, and you’re watching Astrum. Join me today as we explore the fascinating evidence for this ninth planet, the thus far undiscovered Planet X, and explain why some scientists predict that it’s there with 99.6% certainty, while others believe it’s nothing but smoke and mirrors. So, how do we go about discovering new planets in the first place? Discovering planets can be a tricky business. If I was to show you an image like this one, you might immediately get a sense as to why: Can you see a planet here? The answer is probably yes – and I’m not just talking about the Earth along the bottom, which is admittedly a very easy planet to spot. Mars is in this photograph. However, it looks incredibly similar to the stars around it – all are simply sparkling dots in our night sky. The first challenge for mapping out the heavens for any would-be astronomers is identifying which of all these objects is actually a planet in disguise. So, it’s incredibly impressive that early human astronomers were able to figure out which was which more than four millennia ago, using nothing more than careful observation. By watching the night sky every night, and making intricately detailed star maps, Babylonian astronomers were able to chart the motions of these celestial bodies and identify which were orbiting around our solar system, and which remained roughly in place. Stars, being so far away, would not appear to move, unlike the planets which were much closer. Not a bad piece of deduction! This observational method was able to identify the first 6 planets in the Solar system, everything from Mercury to Saturn. However, it fell short of identifying planets past that. The more distant a planet became, the harder it was to spot with the naked eye. The next planet, Uranus, was almost too far away to see. As such, its discovery had to wait until the invention of the telescope, in the early 1600s. Even after that, it took until 1781 before Uranus was officially discovered, and when it happened, it was quite by accident. Astronomer Sir William Herschel was in his garden in England one evening, and was searching for comets using a homemade 6.2 inch telescope. He just stumbled upon Uranus by chance. He initially thought it was a comet, although over time he and other scientists realised that it must have been a planet from signs like its lack of a tail. They named it Uranus after the father of Saturn, who in Roman mythology was the father of Zeus or Jupiter, thus keeping up with the naming convention. Once they knew where Uranus was, astronomers realised that they’d actually seen it before. In star-charts dating as far back as 128BC there were possible references to it, although these all identified it as a star, rather than a planet. It took a telescope to zoom in enough on Uranus to be able to tell the difference, and officially get it recognised as to what it was. Interestingly, here the trend changes. It was not only with a telescope that the final planet Neptune was discovered, but with maths. After a few decades of observing Uranus and plotting out its orbit, a man named Alexis Boulevard published an astronomical table detailing the orbit of Uranus, basing his calculations on Newtonian physics. However, there was a problem. As astronomers watched Uranus, they realised that it failed to follow the path Boulevard had predicted. They spent some time working out why this might be. Maybe they had made some errors in their observations? Maybe Newtonian physics was not correct? It wasn’t until 1845 that a French mathematician named Urbain Le Verrier properly explained the solution: there had to be another planet influencing Uranus. Uranus’ orbit was being perturbed by something. This perturbance could be exactly and precisely predicted mathematically if there was another planet pulling on it, altering its orbit slightly. So detailed were Le Verrier’s calculations that they even told astronomers exactly where this extra planet needed to be for all of this to work. Astronomer Johann Gottfried Galle looked there, and sure enough, to within a single degree of Le Verrier’s calculations, he found Neptune. Just like with Uranus, it quickly turned out that Neptune was not a completely new discovery. Once they knew where it was and where it orbited, astronomers could look back through their records and were able to find other references to it. Although it could not be seen by the naked eye, Galileo managed to spot it with his telescope back in 1612. He even recorded it on a second occasion, and noted that it had strangely moved between the two times of recording, although apparently, he did not appreciate what this meant. In the end, Galileo and others who saw it believed it was simply another star. Only Galle knew that what he was seeing was a planet, and so was credited with the discovery of Neptune. Neptune’s discovery was significant, as it marked the first time a planet had been located in our solar system through mathematical prediction, rather than through observation. It wouldn’t be too long before astronomers tried to do this same thing again. Which brings us to planet 9. Let’s jump forward to 1903. At that time, Percival Lowell published a book where he believed that the existence of Neptune did not sufficiently explain irregularities astronomers were observing in Uranus and other celestial bodies in our solar system. Lowell became convinced that there had to still be another planet out there, something large enough to affect the other planets’ gravities, which he called “Planet X”. Searching for Planet X became a lifelong passion of his. He poured years of his life into the search, and even after his death encouraged others to keep looking for it by donating $1,000,000 in funding towards finding it. His efforts managed to prompt the later discovery of Pluto in 1930, although this small dwarf planet was ruled out from being “Planet X” because it was too small. To this day, after 100 years, Planet X, or Planet 9, still has not been officially discovered. So, why do we think it is there at all? Well, just as it was before Neptune, not all the objects in the solar system are orbiting as we would expect. This was emphasised in 2016 by Astronomers Mike Brown and Konstantin Batygin, who were studying Kuiper Belt Objects. The Kuiper Belt is a region of space out beyond Neptune, covering from 30 to 55 AU from the Sun. Brown and Batygin noted that 14 of these KBOs were clumping in an unusual way at a particular point in their orbit around the sun. They argued that this was evidence that something was bringing them together, attracting them, and pulling them into the orbits that we see. Brown and Batygin continue to claim this theory to this day, and are continuing their search for the planet they believe must be there. According to them, Planet X exists to a 99.6% certainty. If their claim is true, planet X is large. With a mass at least 5 times that of Earth, planet X will most likely orbit between 300 and 520 AU out from the Sun. For a point of reference, this is extremely far out. Neptune orbits 30 AU from the Sun – 1 AU being the distance from the Sun to the Earth. This means that while it takes Neptune 165 years to complete one orbit, it could take the supposed planet X around 10,000 years to complete just a single orbit. From planet X, the sun would appear about as bright as the moon, making it a cold and dark place even during its daytime. There is some debate about whether planet X would have formed within our solar system, or whether it was captured in the sun’s gravitational pull from a passing star. Or perhaps it was a rogue planet, just drifting through space? However, not all astronomers are convinced that planet X exists. In 2020, there were two astronomical surveys that identified objects in the Kuiper Belt – the Outer Solar Systems Origins Survey, and the Dark Energy Survey. Between them, they identified over 1000 KBOs in this space, but did not observe any bunching or strange perturbances in their orbits. This has led astronomers to attribute other factors as the explanation for Brown and Batygin’s observations. Perhaps the 14 bunched objects were just observation bias – after all, these objects are very difficult to spot. Perhaps their bunching just looks like that because of insufficient data? Or perhaps the bunching is real, but there are other explanations, such as gravitational occultation from when Neptune passed through that area, early in the solar system’s history? Most pressingly of all is the pertinent question: If planet X is there, why haven’t we seen it? Thanks to modern computers and telescopes, it is easy to check the areas where planet X is supposed to reside. We have photographed vast swathes of the night sky already in minute detail. And although Le Vellier’s calculations allowed Neptune to be found after just an hour’s searching, no such outcome has happened from Brown and Batygin’s. They have searched through existing astronomical data, and have already examined over half of the possible locations of Planet X. No planet was found in any of those places. Even I myself have participated in a citizen science project on Zooniverse where you can search Gaia data for planet 9, and while this citizen science project has accidentally discovered a whole host of nearby brown dwarfs and stars, planet 9 still eludes us. This does not completely rule out planet X’s existence, though. There are still a few explanations for why the planet remains elusive. With an orbital period of 10,000 years, it is possible that the planet just happens to be hiding in a particular portion of its orbit where it is difficult to spot – for instance, next to a cluster of stars that obscure it with their brightness, or at its aphelion, the furthest point in its orbital arc from the sun, where it would be too dim for all but the largest of telescopes to see. Or, the possibility always exists that we have spotted it. Just like with Uranus and Neptune, perhaps a photograph of Planet 9 already exists, but has simply been misidentified as a star? With so many billions of stars to keep track of, and again with planet X’s ten-thousand year orbit time, it would be forgivable if it took a few years to notice that one star was not in exactly the same place it had been when it was last photographed. And so, the search goes on through at least two methods. Those searching for Planet X have enlisted the help of the Subaru Telescope, a device powerful enough to scour even the hypothetical furthest reaches of planet X’s orbit. If it is out there, within the next 5 years or so it might be spotted. Meanwhile, astronomers like Brown and Batygin continue to run searches of the existing data, hoping to spot the one dim dot amid billions that is ever so slightly out of place. It’s tedious work. However, it’s intriguing. With the last few planetary discoveries, amateur astronomers were instrumental in finding the planets in our solar system. Whether or not they recognised it, both Uranus and Neptune were discovered by people just pointing their telescopes at the sky one night. Of course, the ninth planet might not be there at all. Or it might be so far away that you would need a powerful telescope like Subaru to see it. But maybe not. Whether it’s by scouring the data, or by doing a little amateur astronomy, perhaps it won’t be Brown or Batygin who discover the real ninth planet in our solar system. Perhaps it will be us. So if you think you might want to have go yourself, and want me to do a little tutorial on the Zooniverse citizen science project, let me know in the comments! Personally, I find this kind of thing pretty fun, and who knows, even if we don’t find planet nine, we might just be the first ones to discover something else! You might wonder though how people can even begin to use maths to predict where another planet might be. This is all done through astrophysics, a topic which Brilliant has an amazing dedicated course for on their platform. Amazingly, with this and their scientific thinking course, it can build up your knowledge to the point where the maths behind questions like this can really start making sense, thanks to their interactive and visual puzzles and content. And why I’d highly recommend it so much is because if you understand the ‘whys’ behind what goes on in the universe, my videos will have a whole new level of meaning to you as you watch. You can start for free, and learn at your own pace, be it at home or on the go. To get started, visit brilliant.org/astrum or click on the link in the description, and as a special deal for my viewers, the first 200 of you will get 20% off Brilliant’s annual premium subscription. Thanks for watching! If you found value in this video, please like and share! It really goes a long way. And a big thanks to my patrons and members. If you want to support too, and have your name added to this list, check the links in the description. All the best and see you next time.